Acute Knee Injuries: Use of Decision Rules for Selective Radiograph Ordering

HOWARD B. TANDETER, M.D., and

PESACH SHVARTZMAN, M.D.

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel

MAX A. STEVENS, M.D.

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Family physicians often encounter patients with acute knee trauma. Radiographs of injured knees are commonly ordered, even though fractures are found in only 6 percent of such patients and emergency department physicians can usually discriminate clinically between fracture and nonfracture. Decision rules have been developed to reduce the unnecessary use of radiologic studies in patients with acute knee injury. The Ottawa knee rules and the Pittsburgh decision rules are the latest guidelines for the selective use of radiographs in knee trauma. Application of these rules may lead to a more efficient evaluation of knee injuries and a reduction in health costs without an increase in adverse outcomes. (Am Fam Physician 1999;60:2599-608.)

Family physicians are frequently called on to evaluate patients who have acute knee injuries.1 Each year, knee trauma is also responsible for an estimated 1.3 million visits to emergency departments in the United States.2 The anatomic characteristics of the knee, its exposure to external forces and the functional demands placed on the joint may explain the frequency of injury.

|

Standard emergency medicine textbooks imply that radiographs should be routinely obtained for every patient who presents with a knee injury.3-5 Consequently, radiographs are among the most commonly ordered imaging studies for traumatic injury to the knee joint.6,7 This situation persists despite the absence of clear supporting data and the fact that only 6 percent of patients with knee trauma have a fracture.6-9

Even though emergency department physicians can discriminate clinically between fracture and nonfracture, they order radiographs for most patients with acute knee injury. Reasons for the unnecessary use of radiography include fear of lawsuits, failure to obtain an adequate history and expectations on the part of patients.10-12

|

|

Overuse of radiologic studies has become a significant economic problem in the United States.11,13 Although knee radiographs are relatively inexpensive, high volume of a low-cost test has the same overall financial impact as low volume of a high-cost procedure.14,15 Unnecessary radiation exposure and prolonged waiting times are other reasons to decrease the use of radiologic studies. The application of decision rules for the selective ordering of radiographs may result in a more efficient evaluation of patients with acute knee injuries and may reduce the use of radiography in these patients.

This article briefly reviews the anatomy of the knee joint as well as the most common knee fractures and ligament injuries. Clinical decision rules for ordering diagnostic radiographs following knee injuries are also discussed, with special emphasis given to the guidelines developed in Ottawa, Ontario, and Pittsburgh, along with their potential use in the management of knee injuries.

Anatomy of the Knee

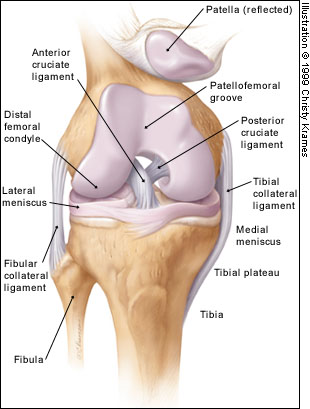

The anatomy and function of the knee are quite complex, and only the basics are described in this article. The osseous structures of the knee include the distal femoral condyles, proximal tibial plateau and patella (Figure 1). The tibial plateau articulates with the femoral condyles, and the patellofemoral groove (located anteriorly between the femoral condyles) accepts the patella. The tibia and patella do not articulate. The gliding motion of the patella across the femur allows smooth extension at the knee and increases the mechanical advantage of the quadriceps.

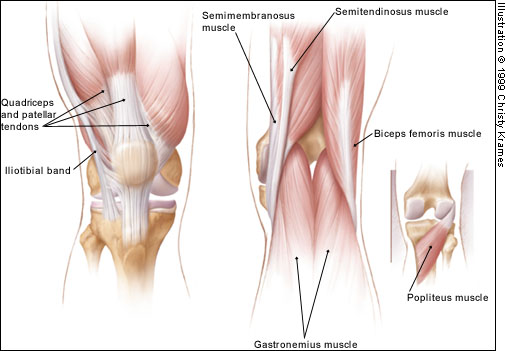

The extra-articular muscle-tendon units include the quadriceps and patellar tendons (responsible for knee extension), medial and lateral hamstrings (chiefly responsible for knee flexion), gastrocnemius muscle, popliteal ligament and iliotibial band (Figure 2).

The extra-articular ligamentous structures include the tibial and fibular collateral ligaments (Figure 1). These ligaments act as the principal extra-articular static stabilizing structures (i.e., they provide stability for the medial and lateral aspects of the knee).

|

|

The intra-articular structures include the medial and lateral menisci and the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (Figure 1). The menisci are fibrocartilaginous wedges that rim and cushion each tibiofemoral articulation. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments provide stability for the knee joint.

|

|

Knee Fractures

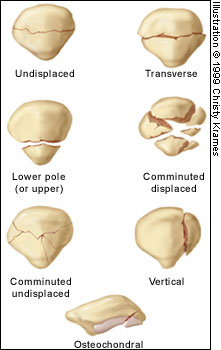

Fractures may occur in the patella, femoral condyles or tibial plateau.16 Patellar fractures are divided into transverse, vertical, upper pole, lower pole, comminuted and osteochondral fractures (Figure 3). Each type can be undisplaced or displaced (Figure 4). The two main mechanisms of patellar fracture are direct trauma to the anterior aspect of the knee or a powerful contraction of the quadriceps muscle (transverse, upper pole and lower pole fractures).

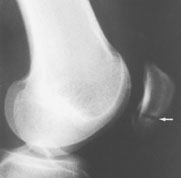

Radiographs are essential to assess traumatic patellar injury. In addition to anteroposterior, notch and lateral views, Merchant and infrapatellar views with the knee in 45 degrees of flexion may be necessary to identify an osteochondral fragment (Figure 5).

Fractures of the femoral condyles involve the distal 9 to 15 cm of the femur (Figure 6). Both the diaphyseal and metaphyseal regions may be involved. Fractures may also show intra-articular extension. Most condylar fractures occur as a result of motor vehicle accidents. Other causes include falling on a flexed knee or falling from a height. In young people, higher energy is necessary for a fracture to occur; consequently, more soft tissue damage is also present. In older patients with osteoporosis, less energy is needed to produce a fracture; therefore, less associated soft tissue damage is present.

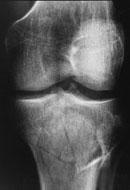

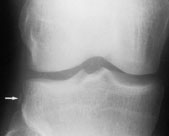

Fractures of the tibial plateau are of special importance because they occur in one of the most important weight-bearing areas (Figure 7). These fractures may involve the metaphysis, epiphysis and/or articular cartilage. The forces that produce fractures in this area are compression, valgus force (outward twisting [away from the midline]) or a combination of both. The fractures primarily involve the lateral plateau, the medial plateau or both structures (bicondylar fractures).

|

|

|

|

|

Knee Ligament Injuries

No validated rules have been formulated for the use of radiography in patients with suspected ligament injuries, but a decision tree can be used as a guide (Figure 8).17 Although plain radiographs may be useful in the initial diagnosis of these injuries, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is becoming the preferred diagnostic method18 and is rapidly replacing other techniques as the study of choice for the evaluation of knee injuries.19 However, the routine use of MRI has been questioned because of its significant cost ($600 to $1,200) and the high accuracy of clinical examination in diagnosing some injuries.20

|

Anterior Cruciate Ligament

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a serious injury, and the

diagnosis may be missed.18

This type of injury can be produced by pure hyperextension or by a combination

of valgus force and external rotation of the tibia relative to the femur.

|

The immediate development of a hemorrhagic effusion is an important point in the history of ACL injury (Figure 9). The stability of the ACL may be clinically assessed with the use of the Lachman test (modified anterior drawer test). More than 90 percent of ACL injuries can be detected based on the history and physical examination.17 However, even the best specialists may fail to recognize the joint laxity of an ACL injury. Therefore, radiographic signs are useful in making the diagnosis.

ACL injury has three main radiographic signs: (1) avulsion of the intercondylar tubercle (Figure 10), (2) anterior displacement of the tibia with respect to the femur, termed the "radiographic drawer sign," and (3) Segond fracture (a thin sliver of bone avulsed from the proximal lateral tibia with the lateral capsular ligament), termed the "lateral capsular sign"16 (Figure 11). Note, however, that these radiographic signs are frequently absent in patients with ACL injuries.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of ruptured ACL is arthroscopy. Compared with this procedure, MRI has a diagnostic accuracy of more than 90 percent. In addition, ultrasound examination has been shown to be a useful and inexpensive mode of detecting a ruptured ACL in the clinical setting of a traumatic hemarthrosis.21

|

|

|

|

Posterior Cruciate Ligament

Injuries of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) are relatively uncommon,

apparently because this is the strongest major knee ligament. The mechanism of

isolated PCL injury is blunt trauma to the anterior proximal tibia

("dashboard injury").

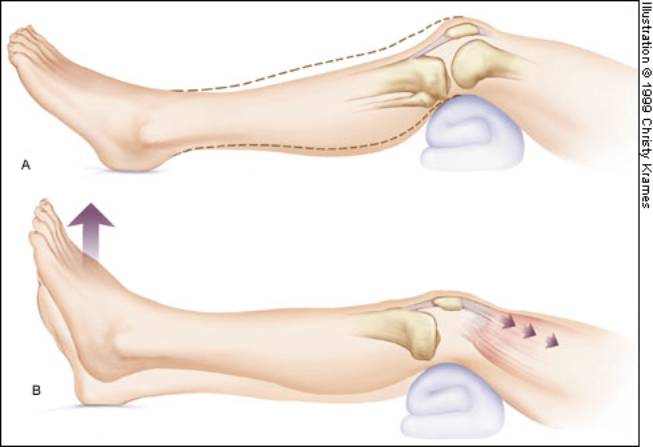

Several maneuvers can be helpful in diagnosing PCL injuries (Figure 12). In one study,22 the gravity sign near extension correctly diagnosed PCL injury in 20 of 24 patients, and active reduction of posterior tibial subluxation correctly identified PCL injury in 18 of 24 patients. The gravity test is performed at 20 degrees of knee flexion. Neither maneuver requires anesthesia.

|

|

Nonetheless, clinical diagnosis may be difficult, and radiographic signs are important.18 The most common radiographic sign of PCL injury is avulsion at the site of the ligament's origin on the posterior tibia (Figure 13). Less commonly, avulsion can be seen at the site of PCL insertion at the medial femoral condyle. When the PCL fails, posterior sagging of the tibia relative to the femur may be seen on the lateral radiograph.

|

|

MRI is accurate in diagnosing PCL injuries. It can also show associated injuries of the ACL and medial collateral ligament (MCL), as well as bone contusions.

Medial Collateral Ligament

Knee injuries involving valgus force, with or without a rotational element, are

suggestive of MCL injury. The physical examination may demonstrate effusion or

local soft tissue swelling and ecchymosis.18

Injuries to the MCL usually occur at the ligament's proximal origin. Therefore,

tenderness is usually localized along the distal femur and extends to the joint

line.17

The major secondary radiographic sign of MCL injury is widening of the medial joint space. A lateral tibial plateau fracture may also suggest MCL injury.

MRI demonstrates MCL injury as well as associated injuries of the medial meniscus, capsule and ACL.

Lateral cCollateral

Ligamentous Domplex

Injuries of the lateral collateral ligamentous complex (LCL) are estimated to

account for only 5 percent of all knee ligament injuries.18,23 Radiographic signs suggesting LCL

injury include lateral joint space widening and medial tibial plateau fracture.18

Decision Rules for Radiography in Acute Knee Injury

For several years, researchers have been working to design protocols that may reduce the number of radiographs used in the evaluation of extremity injuries. A good example of a successful protocol is the one now known as the "Ottawa ankle rules."24-27 Protocols have also been designed for the radiologic evaluation of knee injuries.28-30 The clinical decision rules created in Ottawa and Pittsburgh are the best known guidelines for the appropriate use of radiographs in acute knee injuries (Table 1).

|

Ottawa Knee Rules

Investigators in Ottawa conducted a retrospective chart review of all patients

with acute knee injuries who presented to an emergency department over a

10-month period.8 The knees of

74 percent of these patients were evaluated radiographically, but only 5.2

percent were found to have fractures. All charts were evaluated for the

presence of 11 clinical variables: age, gender, mechanism of injury (blunt

trauma or fall versus twisting), history of swelling, history of deformity,

ability to ambulate (i.e., to walk four steps), swelling, effusion, ligamentous

instability, decreased range of motion and pain on palpation.

Logistic regression analysis found that a fall or blunt trauma mechanism of injury had a sensitivity of 92 percent and a specificity of 57 percent for the presence of a knee fracture.8 The addition of inability to ambulate and age (younger than 12 years and older than 50 years) improved the specificity. The prospective part of the study found that the combination of all three criteria was 100 percent sensitive and 79 percent specific for knee fracture.29

In a later study,27 attending physicians in the emergency departments of two university hospitals assessed every adult patient with an acute knee injury for 23 standardized clinical findings. The Ottawa knee rules were derived from this study. The presence of one or more of these findings would have identified the 68 fractures in the study population. Furthermore, application of the Ottawa knee rules would have led to a 28 percent relative reduction in the use of radiography in the study population.

A prospective validation of the Ottawa knee rules was published in 1996.2 Attending emergency department physicians assessed each patient for standardized clinical variables and determined the need for radiography based on the decision rules. The rules were assessed for their ability to correctly identify the criterion standard, which was fracture of the knee. The study found that the decision rules were 100 percent sensitive for identifying knee fractures, were reliable and acceptable, and had the potential to allow physicians to reduce the use of radiography in patients with acute knee injuries. If the decision rules were negative, the probability of a knee fracture was zero percent.

|

Pittsburgh Decision Rules

The Pittsburgh decision rules for optimizing the use of radiography in patients

with acute knee injuries were presented in 1995.31 A prospective observational study was conducted over a

10-month period in the emergency department of a university hospital. A

standardized closed-question data collection instrument that recorded 12

historical and 26 physical examination criteria was used in the study. A

clinical algorithm for the use of radiography that requires the presence of an

inability to bear weight, an effusion or an ecchymosis was 100 percent

sensitive for the detection of knee fractures. No fractures were found in

patients who did not meet one or more of the criteria. Limiting knee

radiography to patients who met these criteria would have reduced the use of

radiography by 39 percent without missing a fracture.

Comparison of Decision Rules

The Ottawa knee rules and the Pittsburgh decision rules were compared in a

prospective study of patients evaluated in the emergency departments of three

teaching hospitals.32 The Pittsburgh decision rules were 99 percent

sensitive and 60 percent specific for the diagnosis of knee fractures and could

have reduced the use of radiography by 52 percent, with one missed fracture. If

the rules indicated a fracture, 24.1 percent of patients actually had a knee

fracture (positive predictive value); if the rules indicated no fracture, 99.8

percent of patients did not have a knee fracture (negative predictive value).

The Ottawa knee rules were 97 percent sensitive and 27 percent specific for

knee fractures, with three fractures missed. The authors of the comparative

study concluded that the Pittsburgh decision rules were more specific, with no

loss of sensitivity.

The authors thank Daniel Fick, M.D., University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City, for reviewing the manuscript and assisting in the editing process.

Coordinators of this series are Thomas J. Barloon, M.D., associate professor of radiology, and George R. Bergus, M.D., associate professor of family practice, both at the University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City.

The editors of AFP welcome the submission of manuscripts for the Radiologic Decision-Making series. Send submissions to Jay Siwek, M.D., following the guidelines provided in "Information for Authors."

The Authors

HOWARD B. TANDETER, M.D.,

is a lecturer in family medicine at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev,

Beer-Sheva, Israel. After graduating from the Faculty of Medicine at the

University of Buenos Aires, Dr. Tandeter completed a family medicine residency

in Beer-Sheva and an academic fellowship at the University of Toronto, Ontario.

PESACH SHVARTZMAN, M.D.,

is an associate professor and chairman of the Department of Family Medicine at

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He received his medical degree from the

Medical School at the Technion, Haifa, Israel, and completed a family medicine

residency in Afula, Israel. Dr. Shvartzman was a visiting professor at McGill

University Faculty of Medicine, Montreal, Quebec.

MAX A. STEVENS, M.D.,

is currently in private practice at Iowa Lutheran Hospital, Des Moines. He

received his medical degree from the University of Iowa College of Medicine in

Iowa City. After a transitional-year internship at the University of South

Dakota School of Medicine, Sioux Falls, Dr. Stevens completed a residency in

diagnostic radiology at Creighton University School of Medicine and Saint

Joseph Hospital, Omaha. He also completed a fellowship in musculoskeletal

radiology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City.

Address correspondence to Howard B. Tandeter, M.D., Department of Family Medicine, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, P.O. Box 653, Beer-Sheva 84105, Israel. Reprints are not available from the authors.

REFERENCES

1. Shvartzman P, Oren B, Segal Z. X-rays in extremities injury. Fam Physician [Tel Aviv] 1988;15:404-10.

2. Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, Wells GA, McDowell I, Cwinn AA, Smith NA, et al. Prospective validation of a decision rule for the use of radiography in acute knee injuries. JAMA 1996;275:611-5.

3. Simmon RR, Koenigsknecht SJ. Emergency orthopedics: the extremities. 3d ed. Norwalk, Conn.: Appleton & Lange, 1995.

4. Harwood-Nuss A, ed. The clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1991.

5. Callaham ML, ed. Current therapy in emergency medicine. Toronto: Decker, 1987.

6. McConnochie KM, Roghmann KJ, Pasternack J, Monroe DJ, Monaco LP. Prediction rules for selective radiographic assessment of extremity injuries in children and adolescents. 1990;86:45-57.

7. Gratton MC, Salomone JA 3d, Watson WA. Clinically significant radiograph misinterpretations at an emergency medicine residency program. Ann Emerg Med 1990;19:497-502.

8. Stiell IG, Wells GA, McDowell I, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, Quinn JV, et al. Use of radiography in acute knee injuries: need for clinical decision rules. Acad Emerg Med 1995;2:966-73.

9. Gleadhill DN, Thomson JY, Simms P. Can more efficient use be made of x-ray examinations in the accident and emergency department? Br Med J [Clin Res] 1987;294:943-7.

10. Long AE. Radiographic decision-making by the emergency physician. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1985;3:437-46.

11. Hall FM. Overutilization of radiological examinations. Radiology 1976;120:443-8.

12. Brand DA, Frazier WH, Kohlhepp WC, Shea KM, Hoefer AM, Ecker MD, et al. A protocol for selecting patients with injured extremities who need x-rays. N Engl J Med 1982;306:333-9.

13. Abrams HL. The "overutilization" of x-rays. N Engl J Med 1979;300:1213-6.

14. Angell M. Cost containment and the physician. JAMA 1985;254:1203-7.

15. Moloney TW, Rogers DE. Medical technology--a different view of the contentious debate over costs. N Engl J Med 1979;301:1413-9.

16. Weinstein SL, Buckwalter JA, eds. Turek's Orthopaedics, principles and their application. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1994.

17. Smith BW, Green GA. Acute knee injuries: Part II. Diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 1995;51:799-806.

18. Manaster BJ, Ensign MF. Imaging the ligaments of the knee. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging 1991;32:323-66.

19. Stull MA, Nelson MC. The role of MRI in diagnostic imaging of the injured knee. Am Fam Physician 1990;41:489-500.

20. O'Shea KJ, Murphy KP, Heekin RD, Herzwurm PJ. The diagnostic accuracy of history, physical examination, and radiographs in the evaluation of traumatic knee disorders. Am J Sports Med 1996; 24:164-7.

21. Ptasznik R, Feller J, Bartlett J, Fitt G, Mitchell A, Hennessy O. The value of sonography in the diagnosis of traumatic rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995; 164:1461-3.

22. Stšubli HU, Jakob RP. Posterior instability of the knee near extension. A clinical and stress radiographic analysis of acute injuries of the posterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1990;72: 225-30.

23. Newman AP. Meniscal and ligamentous injuries of the knee. Top Emerg Med 1988;10(3):1.

24. Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, Nair RC, McDowell I, Worthington JR. A study to develop clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Ann Emerg Med 1992;21: 384-90.

25. Stiell IG, McKnight RD, Greenberg GH, McDowell I, Nair RC, Wells GA, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa ankle rules. JAMA 1994;271:827-32.

26. Stiell I, Wells G, Laupacis A, Brison R, Verbeek R, Vandemheen K, et al. Multicentre trial to introduce the Ottawa ankle rules for use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Multicentre Ankle Rule Study. BMJ 1995;311:594-7.

27. Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, Wells GA, McKnight RD, Cwinn AA, Cacciotti T, et al. Derivation of a decision rule for the use of radiography in acute knee injuries. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:405-13.

28. Rivara FP, Parish RA, Mueller BA. Extremity injuries in children: predictive value of clinical findings. Pediatrics 1986;78:803-7.

29. Seaberg DC, Jackson R. Clinical decision rule for knee radiographs. Am J Emerg Med 1994;12:541-3.

30. Weber JE, Jackson RE, Peacock WF, Swor RA, Carley R, Larkin GL. Clinical decision rules discriminate between fractures and nonfractures in acute isolated knee trauma. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:429-33.

31. Bauer SJ, Hollander JE, Fuchs SH, Thode HC Jr. A clinical decision rule in the evaluation of acute knee injuries. J Emerg Med 1995;13:611-5.

32. Seaberg DC, Yealy DM, Lukens T, Auble T, Mathias S. Multicenter comparison of two clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute, high-risk knee injuries. Ann Emerg Med 1998;32:8-13.

Copyright

© 1999 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one

printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her

personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be

downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium,

whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the

AAFP. Contact afpserv@aafp.org for

copyright questions and/or permission requests.

December 1, 1999 Contents | AFP Home Page | AAFP Home | Search